We really don’t know where we’re going, but I have a hunch I can’t shake off about where we are right now. Ray Dalio has significantly influenced my macroeconomic thinking, and I will be citing concepts he has written about extensively over the years. We are entering a multi-year period of inflationary deleveraging, with tail risks concentrated in the AI sector. Government policy will attempt to manage the fallout, but structural pressures make disorderly outcomes more likely than policymakers expect. I aim to highlight and illustrate the signals we can expect from policymakers and market sectors, helping us identify which part of the cycle we are likely to find ourselves in.

As always, let’s start with the facts. A year and a half ago, the Federal Funds Rate (FFR) reached a peak of 5.5%. We had an inverted yield curve, risky markets saw liquidity dry up (not to mention the significant amount of liquidity now invested in illiquid assets, such as real estate), and we experienced the first tests of public market weakness in 1HFY25. In Q1 FY25, our debt-to-GDP ratio stood at 120%, indicating we are in the late stage of our debt cycle.

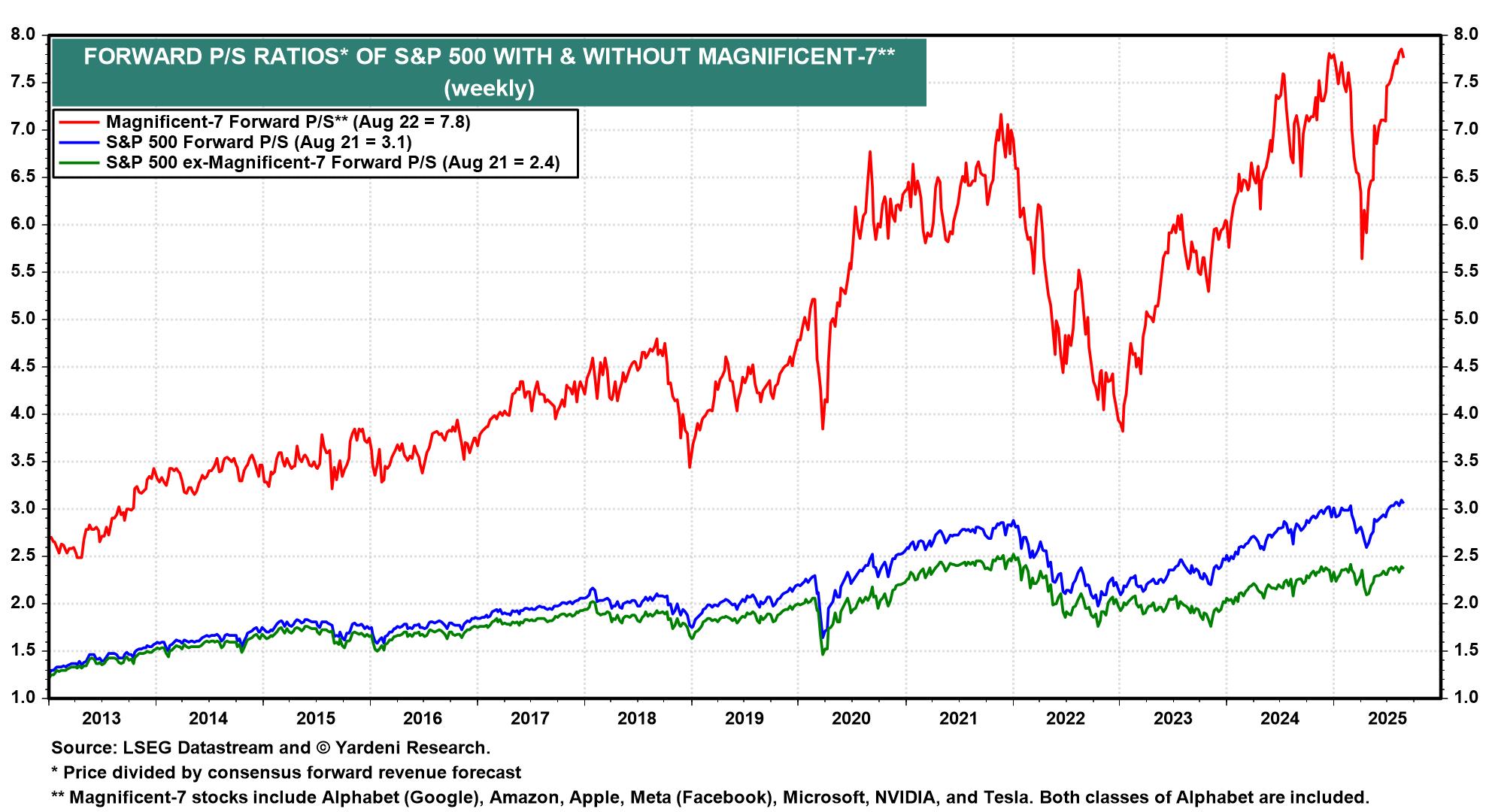

Public markets were justified in selling off. We’re in a stealth recession with inflation and asset bubbles masking the pain. The wealth effect of public markets is distorting people’s perceptions of reality, and the divide between Main Street & Wall Street has never been larger. We cannot look at public markets to determine whether we’re in a bull or bear market in the broader economy. If we net out the Magnificent 7 from the S&P, 493 of the best companies in the US haven’t gone anywhere.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, we’ve experienced several geopolitical, supply chain, and health shocks to our economic system—followed by rapid corrections and subsequent rallies driven by questionable tailwinds in the economy.

AI is an obvious culprit, where valuations are thrown out the window because “It’s different this time, this will change the world.” I admit, AI is powerful, and it will continue to drive GDP growth. Yet, there are peaks and troughs in every cycle, including those in technology. Approximately 95% of tech startups founded during the dot-com bubble no longer exist today, and people lost fortunes betting on those companies.

There isn’t a day that goes by when I call an investor, operator, or analyst, and they aren’t showing me a new way they’re making money. People are making money – it is never the end of the world. The question always is about our positioning relative to the invisible hand.

Policy makers are leaning on short-term financial repression, where they hold real rates below growth/inflation to erode the national debt over time. Their goal is “Beautiful Deleveraging.” This means we continue growing, assets deflate in value slightly, and there is a moderate amount of defaults and restructurings. This means that the pain is evenly distributed throughout the economy.

Nevertheless, smart money is not having it, as we are in the late stage of the long-term debt supercycle. For the massive institution that’s planning its next 100 years of operation, this cycle matters far more than a short-term business cycle, and is why gold and the Swiss Franc are such popular safe havens at the moment.

Policy may aim for a beautiful deleveraging, but structural pressures make an inflationary deleveraging more likely. Our debt burdens will likely remain high; the government will look for “easy way out” options, we will continue to run fiscal deficits, and rely on inflation to reduce real debt loads. Yields will remain volatile, the Fed may try to print more money and spend our way out of this mess as the economy stagnates in real terms.

With the bid to nationalize OpenAI and the successful bid for 10% of Intel’s stock, this signals the government’s willingness to eat bad assets and shield private actors from losses. They will likely then use central banks to fund those asset purchases by printing more money. If nationalization spreads, it shifts pain from private markets to taxpayers, short-circuiting the natural cycle and increasing social instability.

Some argue that it’s in our national defense interests to short-circuit this cycle, but there is a significant chance this backfires further and creates “Disorderly Deleveraging.” Our debt service may spiral out of control faster than policymakers can contain it. Confidence in US monetary policy wavers, leading to increased volatility in the dollar and wider credit spreads. In the event of a disorderly deleveraging, sitting on long-duration treasuries, alternatives, and metals is ideal.

We will fall into this disorder if the AI boom loses momentum due to the failure to materialize efficiencies in enterprise pilot programs, inadequate energy infrastructure to support demand, and the increasing scrutiny regulators have on AI policy as the new technology encroaches on the American white-collar job market.

Investors who chase returns instead of preserving real purchasing power will have their hands tied at the wrong moment. Saying no to more leverage and rotating into hard assets such as commodities and resource equities will drive a more robust portfolio. Bond rotations into TIPS (depending on whether inflation stabilizes or spirals) or global equivalents are preferred as fixed income becomes unattractive.

We strip away the headlines and political noise when making calls on behalf of our firm. The only things that matter are the data, the deals at hand, and what industry leaders are saying behind closed doors. Currently, the picture points clearly to an inflationary deleveraging—stagflation, by another name—with the only meaningful tail risk being the unwinding of the AI trade. Our job isn’t to predict politics, it’s to protect capital while delivering outsized and uncorrelated returns to public benchmarks.

References

- Chart from Yardeni Research. https://yardeni.com/charts/magnificent-7/